mirror of

https://github.com/django-components/django-components.git

synced 2025-09-26 15:39:08 +00:00

chore: init docs

This commit is contained in:

parent

899b9a2738

commit

163b0941c2

49 changed files with 1447 additions and 9 deletions

73

docs/user_guide/commands.md

Normal file

73

docs/user_guide/commands.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,73 @@

|

|||

# Management Command

|

||||

|

||||

You can use the built-in management command `startcomponent` to create a django component. The command accepts the following arguments and options:

|

||||

|

||||

- `name`: The name of the component to create. This is a required argument.

|

||||

|

||||

- `--path`: The path to the components directory. This is an optional argument. If not provided, the command will use the `BASE_DIR` setting from your Django settings.

|

||||

|

||||

- `--js`: The name of the JavaScript file. This is an optional argument. The default value is `script.js`.

|

||||

|

||||

- `--css`: The name of the CSS file. This is an optional argument. The default value is `style.css`.

|

||||

|

||||

- `--template`: The name of the template file. This is an optional argument. The default value is `template.html`.

|

||||

|

||||

- `--force`: This option allows you to overwrite existing files if they exist. This is an optional argument.

|

||||

|

||||

- `--verbose`: This option allows the command to print additional information during component creation. This is an optional argument.

|

||||

|

||||

- `--dry-run`: This option allows you to simulate component creation without actually creating any files. This is an optional argument. The default value is `False`.

|

||||

|

||||

### Management Command Usage

|

||||

|

||||

To use the command, run the following command in your terminal:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

python manage.py startcomponent <name> --path <path> --js <js_filename> --css <css_filename> --template <template_filename> --force --verbose --dry-run

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Replace `<name>`, `<path>`, `<js_filename>`, `<css_filename>`, and `<template_filename>` with your desired values.

|

||||

|

||||

### Management Command Examples

|

||||

|

||||

Here are some examples of how you can use the command:

|

||||

|

||||

### Creating a Component with Default Settings

|

||||

|

||||

To create a component with the default settings, you only need to provide the name of the component:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

python manage.py startcomponent my_component

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This will create a new component named `my_component` in the `components` directory of your Django project. The JavaScript, CSS, and template files will be named `script.js`, `style.css`, and `template.html`, respectively.

|

||||

|

||||

### Creating a Component with Custom Settings

|

||||

|

||||

You can also create a component with custom settings by providing additional arguments:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

python manage.py startcomponent new_component --path my_components --js my_script.js --css my_style.css --template my_template.html

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This will create a new component named `new_component` in the `my_components` directory. The JavaScript, CSS, and template files will be named `my_script.js`, `my_style.css`, and `my_template.html`, respectively.

|

||||

|

||||

### Overwriting an Existing Component

|

||||

|

||||

If you want to overwrite an existing component, you can use the `--force` option:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

python manage.py startcomponent my_component --force

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This will overwrite the existing `my_component` if it exists.

|

||||

|

||||

### Simulating Component Creation

|

||||

|

||||

If you want to simulate the creation of a component without actually creating any files, you can use the `--dry-run` option:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

python manage.py startcomponent my_component --dry-run

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This will simulate the creation of `my_component` without creating any files.

|

||||

117

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/advanced.md

Normal file

117

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/advanced.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,117 @@

|

|||

# Advanced

|

||||

|

||||

## Re-using content defined in the original slot

|

||||

|

||||

Certain properties of a slot can be accessed from within a 'fill' context. They are provided as attributes on a user-defined alias of the targeted slot. For instance, let's say you're filling a slot called 'body'. To access properties of this slot, alias it using the 'as' keyword to a new name -- or keep the original name. With the new slot alias, you can call `<alias>.default` to insert the default content.

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

{% component "calendar" date="2020-06-06" %}

|

||||

{% fill "body" as "body" %}{{ body.default }}. Have a great day!{% endfill %}

|

||||

{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Produces:

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

<div class="calendar-component">

|

||||

<div class="header">

|

||||

Calendar header

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

<div class="body">

|

||||

Today's date is <span>2020-06-06</span>. Have a great day!

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Conditional slots

|

||||

|

||||

_Added in version 0.26._

|

||||

|

||||

In certain circumstances, you may want the behavior of slot filling to depend on

|

||||

whether or not a particular slot is filled.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, suppose we have the following component template:

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

<div class="frontmatter-component">

|

||||

<div class="title">

|

||||

{% slot "title" %}Title{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

<div class="subtitle">

|

||||

{% slot "subtitle" %}{# Optional subtitle #}{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

By default the slot named 'subtitle' is empty. Yet when the component is used without

|

||||

explicit fills, the div containing the slot is still rendered, as shown below:

|

||||

|

||||

```html

|

||||

<div class="frontmatter-component">

|

||||

<div class="title">

|

||||

Title

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

<div class="subtitle">

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This may not be what you want. What if instead the outer 'subtitle' div should only

|

||||

be included when the inner slot is in fact filled?

|

||||

|

||||

The answer is to use the `{% if_filled <name> %}` tag. Together with `{% endif_filled %}`,

|

||||

these define a block whose contents will be rendered only if the component slot with

|

||||

the corresponding 'name' is filled.

|

||||

|

||||

This is what our example looks like with an 'if_filled' tag.

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

<div class="frontmatter-component">

|

||||

<div class="title">

|

||||

{% slot "title" %}Title{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

{% if_filled "subtitle" %}

|

||||

<div class="subtitle">

|

||||

{% slot "subtitle" %}{# Optional subtitle #}{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

{% endif_filled %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Just as Django's builtin 'if' tag has 'elif' and 'else' counterparts, so does 'if_filled'

|

||||

include additional tags for more complex branching. These tags are 'elif_filled' and

|

||||

'else_filled'. Here's what our example looks like with them.

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

<div class="frontmatter-component">

|

||||

<div class="title">

|

||||

{% slot "title" %}Title{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

{% if_filled "subtitle" %}

|

||||

<div class="subtitle">

|

||||

{% slot "subtitle" %}{# Optional subtitle #}{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

{% elif_filled "title" %}

|

||||

...

|

||||

{% else_filled %}

|

||||

...

|

||||

{% endif_filled %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Sometimes you're not interested in whether a slot is filled, but rather that it _isn't_.

|

||||

To negate the meaning of 'if_filled' in this way, an optional boolean can be passed to

|

||||

the 'if_filled' and 'elif_filled' tags.

|

||||

|

||||

In the example below we use `False` to indicate that the content should be rendered

|

||||

only if the slot 'subtitle' is _not_ filled.

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

{% if_filled subtitle False %}

|

||||

<div class="subtitle">

|

||||

{% slot "subtitle" %}{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

{% endif_filled %}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

13

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/context_scope.md

Normal file

13

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/context_scope.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,13 @@

|

|||

# Component context and scope

|

||||

|

||||

By default, components can access context variables from the parent template, just like templates that are included with the `{% include %}` tag. Just like with `{% include %}`, if you don't want the component template to have access to the parent context, add `only` to the end of the `{% component %}` tag):

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

{% component "calendar" date="2015-06-19" only %}{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

NOTE: `{% csrf_token %}` tags need access to the top-level context, and they will not function properly if they are rendered in a component that is called with the `only` modifier.

|

||||

|

||||

Components can also access the outer context in their context methods by accessing the property `outer_context`.

|

||||

|

||||

You can also set `context_behavior` to `isolated` to make all components isolated by default. This is useful if you want to make sure that components don't accidentally access the outer context.

|

||||

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,56 @@

|

|||

# Create your first component

|

||||

|

||||

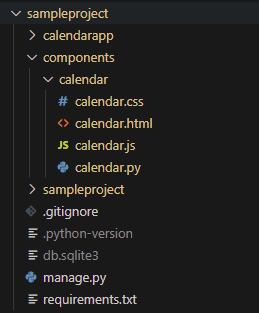

A component in django-components is the combination of four things: CSS, Javascript, a Django template, and some Python code to put them all together.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Start by creating empty files in the structure above.

|

||||

|

||||

First you need a CSS file. Be sure to prefix all rules with a unique class so they don't clash with other rules.

|

||||

|

||||

```css title="[project root]/components/calendar/style.css"

|

||||

.calendar-component { width: 200px; background: pink; }

|

||||

.calendar-component span { font-weight: bold; }

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Then you need a javascript file that specifies how you interact with this component. You are free to use any javascript framework you want. A good way to make sure this component doesn't clash with other components is to define all code inside an anonymous function that calls itself. This makes all variables defined only be defined inside this component and not affect other components.

|

||||

|

||||

```js title="[project root]/components/calendar/script.js"

|

||||

(function(){

|

||||

if (document.querySelector(".calendar-component")) {

|

||||

document.querySelector(".calendar-component").onclick = function(){ alert("Clicked calendar!"); };

|

||||

}

|

||||

})()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Now you need a Django template for your component. Feel free to define more variables like `date` in this example. When creating an instance of this component we will send in the values for these variables. The template will be rendered with whatever template backend you've specified in your Django settings file.

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango title="[project root]/components/calendar/calendar.html"

|

||||

<div class="calendar-component">Today's date is <span>{{ date }}</span></div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Finally, we use django-components to tie this together. Start by creating a file called `calendar.py` in your component calendar directory. It will be auto-detected and loaded by the app.

|

||||

|

||||

Inside this file we create a Component by inheriting from the Component class and specifying the context method. We also register the global component registry so that we easily can render it anywhere in our templates.

|

||||

|

||||

```python title="[project root]/components/calendar/calendar.py"

|

||||

from django_components import component

|

||||

|

||||

@component.register("calendar")

|

||||

class Calendar(component.Component):

|

||||

# Templates inside `[your apps]/components` dir and `[project root]/components` dir will be automatically found. To customize which template to use based on context

|

||||

# you can override def get_template_name() instead of specifying the below variable.

|

||||

template_name = "calendar.html"

|

||||

|

||||

# This component takes one parameter, a date string to show in the template

|

||||

def get_context_data(self, date):

|

||||

return {

|

||||

"date": date,

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

class Media:

|

||||

css = "style.css"

|

||||

js = "script.js"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

And voilà!! We've created our first component.

|

||||

22

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/middleware.md

Normal file

22

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/middleware.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,22 @@

|

|||

# Setting Up `ComponentDependencyMiddleware`

|

||||

|

||||

[`ComponentDependencyMiddleware`][django_components.middleware.ComponentDependencyMiddleware] is a Django middleware designed to manage and inject CSS/JS dependencies for rendered components dynamically. It ensures that only the necessary stylesheets and scripts are loaded in your HTML responses, based on the components used in your Django templates.

|

||||

|

||||

To set it up, add the middleware to your [`MIDDLEWARE`][] in settings.py:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

MIDDLEWARE = [

|

||||

# ... other middleware classes ...

|

||||

'django_components.middleware.ComponentDependencyMiddleware'

|

||||

# ... other middleware classes ...

|

||||

]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Then, enable `RENDER_DEPENDENCIES` in setting.py:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

COMPONENTS = {

|

||||

"RENDER_DEPENDENCIES": True,

|

||||

# ... other component settings ...

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,36 @@

|

|||

# Using single-file components

|

||||

|

||||

Components can also be defined in a single file, which is useful for small components. To do this, you can use the `template`, `js`, and `css` class attributes instead of the `template_name` and `Media`. For example, here's the calendar component from above, defined in a single file:

|

||||

|

||||

```python title="[project root]/components/calendar.py"

|

||||

from django_components import component

|

||||

from django_components import types as t

|

||||

|

||||

@component.register("calendar")

|

||||

class Calendar(component.Component):

|

||||

def get_context_data(self, date):

|

||||

return {

|

||||

"date": date,

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

template: t.django_html = """

|

||||

<div class="calendar-component">Today's date is <span>{{ date }}</span></div>

|

||||

"""

|

||||

|

||||

css: t.css = """

|

||||

.calendar-component { width: 200px; background: pink; }

|

||||

.calendar-component span { font-weight: bold; }

|

||||

"""

|

||||

|

||||

js: t.js = """

|

||||

(function(){

|

||||

if (document.querySelector(".calendar-component")) {

|

||||

document.querySelector(".calendar-component").onclick = function(){ alert("Clicked calendar!"); };

|

||||

}

|

||||

})()

|

||||

"""

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This makes it easy to create small components without having to create a separate template, CSS, and JS file.

|

||||

|

||||

Note that the `t.django_html`, `t.css`, and `t.js` types are used to specify the type of the template, CSS, and JS files, respectively. This is not necessary, but if you're using VSCode with the [Python Inline Source Syntax Highlighting](https://marketplace.visualstudio.com/items?itemName=samwillis.python-inline-source) extension, it will give you syntax highlighting for the template, CSS, and JS.

|

||||

37

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/use_component.md

Normal file

37

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/use_component.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,37 @@

|

|||

|

||||

# Use the component in a template

|

||||

|

||||

First load the [`component_tags`][django_components.templatetags.component_tags] tag library, then use the `component_[js/css]_dependencies` and [`component`][django_components.templatetags.component_tags.do_component] tags to render the component to the page.

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

{% load component_tags %}

|

||||

<!DOCTYPE html>

|

||||

<html>

|

||||

<head>

|

||||

<title>My example calendar</title>

|

||||

{% component_css_dependencies %}

|

||||

</head>

|

||||

<body>

|

||||

{% component "calendar" date="2015-06-19" %}{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

{% component_js_dependencies %}

|

||||

</body>

|

||||

<html>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The output from the above template will be:

|

||||

|

||||

```html

|

||||

<!DOCTYPE html>

|

||||

<html>

|

||||

<head>

|

||||

<title>My example calendar</title>

|

||||

<link href="style.css" type="text/css" media="all" rel="stylesheet">

|

||||

</head>

|

||||

<body>

|

||||

<div class="calendar-component">Today's date is <span>2015-06-19</span></div>

|

||||

<script src="script.js"></script>

|

||||

</body>

|

||||

<html>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This makes it possible to organize your front-end around reusable components. Instead of relying on template tags and keeping your CSS and Javascript in the static directory.

|

||||

190

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/using_slots.md

Normal file

190

docs/user_guide/creating_using_components/using_slots.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,190 @@

|

|||

|

||||

# Using slots in templates

|

||||

|

||||

_New in version 0.26_:

|

||||

|

||||

- The `slot` tag now serves only to declare new slots inside the component template.

|

||||

- To override the content of a declared slot, use the newly introduced `fill` tag instead.

|

||||

- Whereas unfilled slots used to raise a warning, filling a slot is now optional by default.

|

||||

- To indicate that a slot must be filled, the new `required` option should be added at the end of the `slot` tag.

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Components support something called 'slots'.

|

||||

When a component is used inside another template, slots allow the parent template to override specific parts of the child component by passing in different content.

|

||||

This mechanism makes components more reusable and composable.

|

||||

|

||||

In the example below we introduce two block tags that work hand in hand to make this work. These are...

|

||||

|

||||

- `{% slot <name> %}`/`{% endslot %}`: Declares a new slot in the component template.

|

||||

- `{% fill <name> %}`/`{% endfill %}`: (Used inside a `component` tag pair.) Fills a declared slot with the specified content.

|

||||

|

||||

Let's update our calendar component to support more customization. We'll add `slot` tag pairs to its template, _calendar.html_.

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

<div class="calendar-component">

|

||||

<div class="header">

|

||||

{% slot "header" %}Calendar header{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

<div class="body">

|

||||

{% slot "body" %}Today's date is <span>{{ date }}</span>{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

When using the component, you specify which slots you want to fill and where you want to use the defaults from the template. It looks like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

{% component "calendar" date="2020-06-06" %}

|

||||

{% fill "body" %}Can you believe it's already <span>{{ date }}</span>??{% endfill %}

|

||||

{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Since the header block is unspecified, it's taken from the base template. If you put this in a template, and pass in `date=2020-06-06`, this is what gets rendered:

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

<div class="calendar-component">

|

||||

<div class="header">

|

||||

Calendar header

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

<div class="body">

|

||||

Can you believe it's already <span>2020-06-06</span>??

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

As you can see, component slots lets you write reusable containers that you fill in when you use a component. This makes for highly reusable components that can be used in different circumstances.

|

||||

|

||||

It can become tedious to use `fill` tags everywhere, especially when you're using a component that declares only one slot. To make things easier, `slot` tags can be marked with an optional keyword: `default`. When added to the end of the tag (as shown below), this option lets you pass filling content directly in the body of a `component` tag pair – without using a `fill` tag. Choose carefully, though: a component template may contain at most one slot that is marked as `default`. The `default` option can be combined with other slot options, e.g. `required`.

|

||||

|

||||

Here's the same example as before, except with default slots and implicit filling.

|

||||

|

||||

The template:

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

<div class="calendar-component">

|

||||

<div class="header">

|

||||

{% slot "header" %}Calendar header{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

<div class="body">

|

||||

{% slot "body" default %}Today's date is <span>{{ date }}</span>{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Including the component (notice how the `fill` tag is omitted):

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

{% component "calendar" date="2020-06-06" %}

|

||||

Can you believe it's already <span>{{ date }}</span>??

|

||||

{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The rendered result (exactly the same as before):

|

||||

|

||||

```html

|

||||

<div class="calendar-component">

|

||||

<div class="header">

|

||||

Calendar header

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

<div class="body">

|

||||

Can you believe it's already <span>2020-06-06</span>??

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

You may be tempted to combine implicit fills with explicit `fill` tags. This will not work. The following component template will raise an error when compiled.

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

{# DON'T DO THIS #}

|

||||

{% component "calendar" date="2020-06-06" %}

|

||||

{% fill "header" %}Totally new header!{% endfill %}

|

||||

Can you believe it's already <span>{{ date }}</span>??

|

||||

{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

By contrast, it is permitted to use `fill` tags in nested components, e.g.:

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

{% component "calendar" date="2020-06-06" %}

|

||||

{% component "beautiful-box" %}

|

||||

{% fill "content" %} Can you believe it's already <span>{{ date }}</span>?? {% endfill %}

|

||||

{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This is fine too:

|

||||

|

||||

```htmldjango

|

||||

{% component "calendar" date="2020-06-06" %}

|

||||

{% fill "header" %}

|

||||

{% component "calendar-header" %}

|

||||

Super Special Calendar Header

|

||||

{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

{% endfill %}

|

||||

{% endcomponent %}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Components as views

|

||||

|

||||

_New in version 0.34_

|

||||

|

||||

Components can now be used as views. To do this, [`Component`][django_components.component.Component] subclasses Django's [`View`][] class. This means that you can use all of the [methods](https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/5.0/ref/class-based-views/base/#view) of `View` in your component. For example, you can override `get` and `post` to handle GET and POST requests, respectively.

|

||||

|

||||

In addition, [`Component`][django_components.component.Component] now has a [`render_to_response`][django_components.component.Component.render_to_response] method that renders the component template based on the provided context and slots' data and returns an [`HttpResponse`][django.http.HttpResponse] object.

|

||||

|

||||

Here's an example of a calendar component defined as a view:

|

||||

|

||||

```python title="[project root]/components/calendar.py"

|

||||

from django_components import component

|

||||

|

||||

@component.register("calendar")

|

||||

class Calendar(component.Component):

|

||||

|

||||

template = """

|

||||

<div class="calendar-component">

|

||||

<div class="header">

|

||||

{% slot "header" %}{% endslot %}

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

<div class="body">

|

||||

Today's date is <span>{{ date }}</span>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

"""

|

||||

|

||||

def get(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

|

||||

context = {

|

||||

"date": request.GET.get("date", "2020-06-06"),

|

||||

}

|

||||

slots = {

|

||||

"header": "Calendar header",

|

||||

}

|

||||

return self.render_to_response(context, slots)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Then, to use this component as a view, you should create a `urls.py` file in your components directory, and add a path to the component's view:

|

||||

|

||||

```python title="[project root]/components/urls.py"

|

||||

from django.urls import path

|

||||

from calendar import Calendar

|

||||

|

||||

urlpatterns = [

|

||||

path("calendar/", Calendar.as_view()),

|

||||

]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Remember to add `__init__.py` to your components directory, so that Django can find the `urls.py` file.

|

||||

|

||||

Finally, include the component's urls in your project's `urls.py` file:

|

||||

|

||||

```python title="[project root]/urls.py"

|

||||

from django.urls import include, path

|

||||

|

||||

urlpatterns = [

|

||||

path("components/", include("components.urls")),

|

||||

]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Note: slots content are automatically escaped by default to prevent XSS attacks. To disable escaping, set `escape_slots_content=False` in the `render_to_response` method. If you do so, you should make sure that any content you pass to the slots is safe, especially if it comes from user input.

|

||||

|

||||

If you're planning on passing an HTML string, check Django's use of [`format_html`](https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/5.0/ref/utils/#django.utils.html.format_html) and [`mark_safe`](https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/5.0/ref/utils/#django.utils.safestring.mark_safe).

|

||||

0

docs/user_guide/getting_started.md

Normal file

0

docs/user_guide/getting_started.md

Normal file

1

docs/user_guide/index.md

Normal file

1

docs/user_guide/index.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1 @@

|

|||

[TOC]

|

||||

71

docs/user_guide/installation.md

Normal file

71

docs/user_guide/installation.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,71 @@

|

|||

# Installation

|

||||

|

||||

Install the app into your environment:

|

||||

|

||||

> ```pip install django-components```

|

||||

|

||||

Then add the app into [`INSTALLED_APPS`][INSTALLED_APPS] in settings.py

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

INSTALLED_APPS = [

|

||||

...,

|

||||

'django_components',

|

||||

]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Modify [`TEMPLATES`][TEMPLATES] section of settings.py as follows:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

- *Remove `'APP_DIRS': True,`*

|

||||

- add `loaders` to [`OPTIONS`][TEMPLATES-OPTIONS] list and set it to following value:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

TEMPLATES = [

|

||||

{

|

||||

...,

|

||||

'OPTIONS': {

|

||||

'context_processors': [

|

||||

...

|

||||

],

|

||||

'loaders':[(

|

||||

'django.template.loaders.cached.Loader', [

|

||||

'django.template.loaders.filesystem.Loader',

|

||||

'django.template.loaders.app_directories.Loader',

|

||||

'django_components.template_loader.Loader',

|

||||

]

|

||||

)],

|

||||

},

|

||||

},

|

||||

]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Modify [`STATICFILES_DIRS`][STATICFILES_DIRS] (or add it if you don't have it) so django can find your static JS and CSS files:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

STATICFILES_DIRS = [

|

||||

...,

|

||||

os.path.join(BASE_DIR, "components"),

|

||||

]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## _Optional_: Load django-components in all templates

|

||||

|

||||

To avoid loading the app in each template using ``` {% load django_components %} ```, you can add the tag as a 'builtin' in settings.py

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

TEMPLATES = [

|

||||

{

|

||||

...,

|

||||

'OPTIONS': {

|

||||

'context_processors': [

|

||||

...

|

||||

],

|

||||

'builtins': [

|

||||

'django_components.templatetags.component_tags',

|

||||

]

|

||||

},

|

||||

},

|

||||

]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Read on to find out how to build your first component!

|

||||

29

docs/user_guide/logging_debugging.md

Normal file

29

docs/user_guide/logging_debugging.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,29 @@

|

|||

# Logging and debugging

|

||||

|

||||

Django components supports [logging with Django](https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/5.0/howto/logging/#logging-how-to). This can help with troubleshooting.

|

||||

|

||||

To configure logging for Django components, set the `django_components` logger in `LOGGING` in `settings.py` (below).

|

||||

|

||||

Also see the [`settings.py` file in sampleproject](https://github.com/EmilStenstrom/django-components/tree/master/sampleproject/sampleproject/settings.py) for a real-life example.

|

||||

|

||||

```py

|

||||

import logging

|

||||

import sys

|

||||

|

||||

LOGGING = {

|

||||

'version': 1,

|

||||

'disable_existing_loggers': False,

|

||||

"handlers": {

|

||||

"console": {

|

||||

'class': 'logging.StreamHandler',

|

||||

'stream': sys.stdout,

|

||||

},

|

||||

},

|

||||

"loggers": {

|

||||

"django_components": {

|

||||

"level": logging.DEBUG,

|

||||

"handlers": ["console"],

|

||||

},

|

||||

},

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

15

docs/user_guide/requirements_compatibility.md

Normal file

15

docs/user_guide/requirements_compatibility.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,15 @@

|

|||

|

||||

# Compatibility and requirements

|

||||

|

||||

Django-components supports all <a href="https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/dev/faq/install/#what-python-version-can-i-use-with-django">officially supported versions</a> of Django and Python.

|

||||

|

||||

| Python version | Django version |

|

||||

|----------------|--------------------------|

|

||||

| 3.7 | 3.2 |

|

||||

| 3.8 | 3.2, 4.0, 4.1, 4.2 |

|

||||

| 3.9 | 3.2, 4.0, 4.1, 4.2 |

|

||||

| 3.10 | 3.2, 4.0, 4.1, 4.2, 5.0 |

|

||||

| 3.11 | 4.1, 4.2, 5.0 |

|

||||

| 3.12 | 4.2, 5.0 |

|

||||

|

||||

For each version of Django and Python, we recommend using the latest micro release (A.B.C).

|

||||

30

docs/user_guide/security.md

Normal file

30

docs/user_guide/security.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,30 @@

|

|||

|

||||

# Security notes 🚨

|

||||

|

||||

*You are advised to read this section before using django-components in production.*

|

||||

|

||||

### Static files

|

||||

|

||||

Components can be organized however you prefer.

|

||||

That said, our prefered way is to keep the files of a component close together by bundling them in the same directory.

|

||||

This means that files containing backend logic, such as Python modules and HTML templates, live in the same directory as static files, e.g. JS and CSS.

|

||||

|

||||

If your are using [`django.contrib.staticfiles`][] to collect static files, no distinction is made between the different kinds of files.

|

||||

As a result, your Python code and templates may inadvertently become available on your static file server.

|

||||

You probably don't want this, as parts of your backend logic will be exposed, posing a __potential security vulnerability__.

|

||||

|

||||

As of *v0.27*, django-components ships with an additional installable app *[`django_components.safer_staticfiles`][]*.

|

||||

It is a drop-in replacement for *[`django.contrib.staticfiles`][]*.

|

||||

Its behavior is 100% identical except it ignores .py and .html files, meaning these will not end up on your static files server.

|

||||

To use it, add it to [`INSTALLED_APPS`][] and remove [`django.contrib.staticfiles`].

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

INSTALLED_APPS = [

|

||||

# 'django.contrib.staticfiles', # <-- REMOVE

|

||||

'django_components',

|

||||

'django_components.safer_staticfiles' # <-- ADD

|

||||

]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

If you are on an older version of django-components, your alternatives are a) passing `--ignore <pattern>` options to the _collecstatic_ CLI command, or b) defining a subclass of `StaticFilesConfig`.

|

||||

Both routes are described in the official [docs of the _staticfiles_ app](https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.2/ref/contrib/staticfiles/#customizing-the-ignored-pattern-list).

|

||||

58

docs/user_guide/settings.md

Normal file

58

docs/user_guide/settings.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,58 @@

|

|||

|

||||

# Available settings

|

||||

|

||||

All library settings are handled from a global `COMPONENTS` variable that is read from settings.py. By default you don't need it set, there are reasonable defaults.

|

||||

|

||||

## Configure the module where components are loaded from

|

||||

|

||||

Configure the location where components are loaded. To do this, add a `COMPONENTS` variable to you settings.py with a list of python paths to load. This allows you to build a structure of components that are independent from your apps.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

COMPONENTS = {

|

||||

"libraries": [

|

||||

"mysite.components.forms",

|

||||

"mysite.components.buttons",

|

||||

"mysite.components.cards",

|

||||

],

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Disable autodiscovery

|

||||

|

||||

If you specify all the component locations with the setting above and have a lot of apps, you can (very) slightly speed things up by disabling autodiscovery.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

COMPONENTS = {

|

||||

"autodiscover": False,

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Tune the template cache

|

||||

|

||||

Each time a template is rendered it is cached to a global in-memory cache (using Python's lru_cache decorator). This speeds up the next render of the component. As the same component is often used many times on the same page, these savings add up. By default the cache holds 128 component templates in memory, which should be enough for most sites. But if you have a lot of components, or if you are using the `template` method of a component to render lots of dynamic templates, you can increase this number. To remove the cache limit altogether and cache everything, set template_cache_size to `None`.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

COMPONENTS = {

|

||||

"template_cache_size": 256,

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Isolate components' context by default

|

||||

|

||||

If you'd like to prevent components from accessing the outer context by default, you can set the `context_behavior` setting to `isolated`. This is useful if you want to make sure that components don't accidentally access the outer context.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

COMPONENTS = {

|

||||

"context_behavior": "isolated",

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Middleware

|

||||

|

||||

RENDER_DEPENDENCIES: If you are using the `ComponentDependencyMiddleware` middleware, you can enable or disable it here.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

COMPONENTS = {

|

||||

"RENDER_DEPENDENCIES": True,

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

Loading…

Add table

Add a link

Reference in a new issue